I saw a chef fly like Superman, levitating in the air, no cape.

This flight happened inside a Chicago brick two-flat built in 1891 originally owned by a man named H.N. Kiefer. Historical record does not tell us much of Kiefer, but you may recognize the family name of the current owners: Trotter.

Yes, that Trotter.

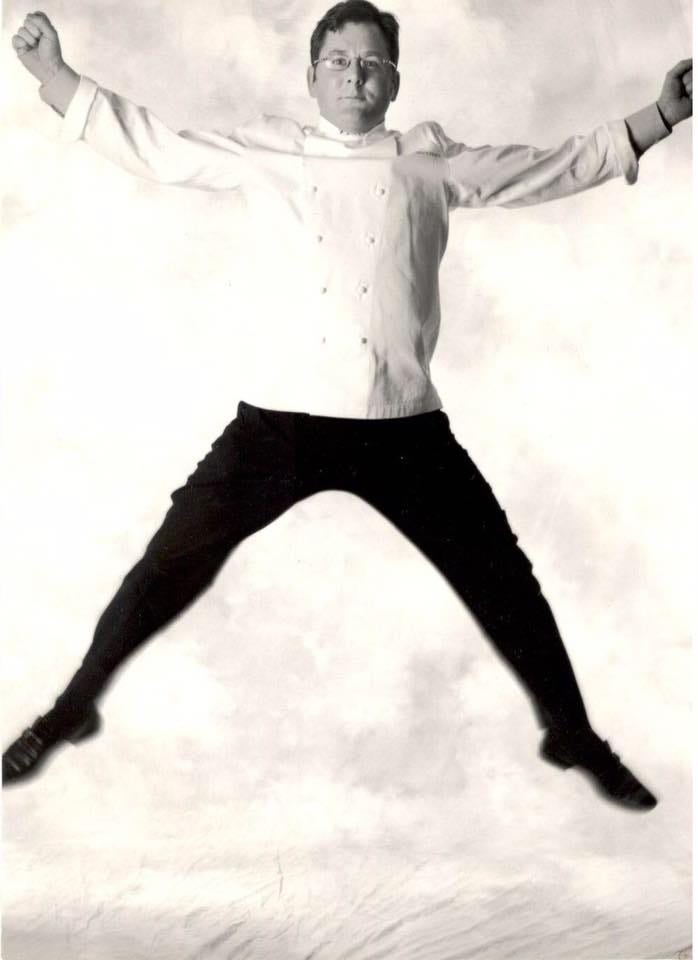

And there he is, chef Charlie, right on the granite bar top at 816 W. Armitage, flying, just like I said.

Trotter wasn’t actually in the room. No, what I’m describing is just a photo of Charlie taken for one of the many thousands of pieces written about him. I know. You feel duped. But, trust me, Trotter does actually fly in this story.

We’ll get there.

Across from the bar where that photo sits still hangs a massive portrait of Trotter that follows you around the room, eyes boring into your soul no matter where you stand, which makes you feel like he is still here.

Back to the photo of Charlie in flight. Trotter asked a photographer to capture him jumping on a neighbor’s trampoline for a shoot. That the philosophical, perceived by those who didn’t know him as reserved (he was apparently wicked funny and down for anything that upended people’s expectations according to his son Dylan) Trotter was flying is kind of fantastical, but that wasn’t even the oddest aspect of this image. It’s more that the guy who questioned and challenged almost everything was wearing a double-breasted white chef coat, a uniform sketched by chef Marie-Antoine Carême in 1822.

I realized that chef Grant Achatz of The Alinea Group, purveyor of edible balloons and exploding truffle ravioli too also wore a traditional coat. I asked Achatz why he thought Charlie did and why he himself, an innovator in most other things, chose that uniform.

Achatz said, “He (Charlie) mostly wore a dress shirt under the coat … For me it was the best looking, all the others are black or European styled which looks like an F1 suit. Kinda like Italian shoes, very gaudy IMO. But mostly I liked the connection to traditionalism and TFL [The French Laundry].”

This story is ultimately about the connection of two of Chicago’s most innovative culinarians, Achatz and Trotter. Both are radical but they have a strong kinship to the foundations of cuisine.

Visiting 816 W. Armitage

In this moment though, I was standing in Charlie’s history. I was a little afraid to revisit the old Trotter’s restaurant space. Not because I believe in the supernatural. My childhood home sat next door to a cemetery.

I’m one of the people in this world with a high statistical probability of seeing a specter. No, I think I was just reluctant to muddle the memory I believe I really wanted of this place, my meal at Trotter’s in its heyday in January of 2003.

Walking into the space in September of 2024, my nostrils flare. I can smell the waft of Honeycrisp apples in my brain, a crate of which had been placed over a heating grate to perfume the foyer in January of 2003, the first and only time I dined at Trotter’s. This deployment of aroma apart from the plate was fairly novel idea in the 1990s.

Achatz would also add accessory aromas to dishes, setting oak leaves on fire with a blowtorch as a garnish for his pheasant dish to invoke the autumn of his Michigan childhood. Achatz came to this idea not directly through Trotter but by watching Thomas Keller throw an aromatic spice blend on a squab dish and by eating a dish at El Bulli where Ferran Adria asked guests to smell a vanilla bean before taking a bite of mashed potatoes larded with sugar, cream, and butter, to make you think you were eating a custard.

The evening I ate at Trotter’s in 2003 I didn’t see the kitchen. I was in my twenties. I didn’t know you could request things like post-dinner tours. Even if I had, I probably would have been scared to ask. I could barely afford the regular meal. I certainly didn’t have the lucre for the kitchen table. I’m not sure I even knew what that was anyway. A lot of people didn’t, because Trotter was the first to have one.

But here in 2024 on a warm afternoon, Trotter’s son Dylan gave me something I didn’t know I needed, the gift of walking back into a temple of culinary gladiators, some names you recognize and some you may not:

Merges, Segal, Duffy, Cantu, Erlich, Shields, Tellez, Lopez, Tentori, Watkins, Kim (Bill and Beverly), Zernich-Worsham, Thomas, Spellman, Houde, Lefevre, Gosset, Bowles, Schmeiding, Sandoval, Signorio, and Stone. I’m missing a million people, but you get the idea.

The kitchen at 816 W. Armitage is still lined in a Frank Gehry-level of gleaming stainless steel. An aircraft carrier of cooking ranges, a $200,000 Bonnet installed in 1995 during a renovation eight years after the restaurant opened still fires up. The most famous restaurant figure in Chicago prior to Trotter, Gordon Sinclair owner of Gordon and Sinclair’s restaurants, the guy who Charlie first worked for, said of this oven, “He paid more for that range than I did for Gordon restaurant.”

Old copper pans hang over the prep tables the way they did when the last chefs laid them there after the last night of service in August of 2012. I shake out of this daydream to find Dylan Trotter gesturing at the vegetable station with the reverence of a Vatican guide.

A massive stock kettle is here now too, but it left this room for a decade, to a North Shore home. It was one of the few items auctioned off before Trotter ceremoniously cancelled his own restaurant liquidation mid-auction.

Did the auction winner make massive amounts of veal stock for his family? Did he mount it below a Miller High Life-neon in his man cave, pointing it out to friends before they whipped out cigars and whiskey for a round of weekend poker?

Dylan wasn’t sure. But I guess it doesn’t matter, because it’s back here, in its rightful place. Except for minor grout work repair on the rusty red tile floor that Dylan is in the middle of finishing, you could cook here now. Maybe someone will soon.

I’m not gonna recount every detail of the Trotter story. If you really want to know, it’s all there on the internet. Although, maybe it’s not. I recorded a podcast with Dylan the afternoon I visited the old restaurant space, and after we were done he said something that I’ve been thinking about now for a week which is that when you have a big public figure like Charlie, who also happens to be your dad, everyone’s got a story, and that many of those stories become like a game of telephone, spiraling in hyperbole with each re-telling.

Dealing With History

I feel like I’d been complicit in this game, not maliciously, but certainly subconsciously. I wrote a piece a few years ago where I speculated that Charlie who believed deeply in the Michelin rating because of his love of the three star Michelin-holding Swiss chef Frédy Girardet, was maybe broken spiritually because he’d only gotten two stars by the time Michelin came to Chicago.

I’d also suggested that maybe Trotter had been depressed by the closing of the restaurant. As Dylan told it, his dad was self-actualizing at this time, reinventing himself, excited to be enrolling at the University of Chicago to study philosophy. There was some erratic behavior, but Dylan said it wasn’t because of substance abuse as some had speculated, but as a result of a series of health-related incidents including a stroke.

By the way, this is not a way of explaining away any controversy around Trotter. It’s well-established that Charlie’s management style which allowed him to create one of the greatest American restaurants in history was about extracting the most from each individual.

Sometimes that meant mind games. Sometimes that meant brutal 18 hour shifts. Sometimes that meant making you work the seafood station even though you have a shellfish allergy, like Trotter once did of chef Curtis Duffy from Ever.

Was this cruel or intentional? It did force Duffy to ask his fellow cooks to taste his work, arguably an early education in how to delegate responsibility and trust your teammates. I’m not saying people didn’t suffer mentally. But the Trotter story is not a black and white one of a sadistic tyrant.

Dylan says Trotter played chess with him a lot as a kid during pre-service. Sometimes Charlie would show up at nearby Oz Park near the restaurant (the one with all the Wizard of Oz statues in Chicago’s Lincoln Park neighborhood) to shoot hoops with Dylan and his friends. Fresh off business meetings and interviews Trotter would pull off a wicked jump shot while wearing a full suit.

Charlie would invite Dylan and his friends to dine for free at the restaurant whenever random tables opened up. The ragtag group would wear surplus oversized blazers usually reserved for guests who forgot to bring their own.

Sometime Charlie would just walk into the Subway around the corner and tell random Lincoln Park high school students to drop their sandwiches and come back to the restaurant for a better meal.

Thousands if not tens of thousands of school kids got to eat in Charlie’s test kitchen next door at 814 W. Armitage for free. Many chefs ended up going to culinary school on scholarships paid for by Trotter foundation.

If you were a chef at any level and Charlie met you, there’s a high chance he sent you a thank you note and an autographed copy of his cookbook. He was legendarily generous to random strangers as well as his guests.

Giuseppe Tentori of GT Prime who once worked as Trotter’s chef de cuisine said, “Some nights, this was before Charlie realized foie gras farming was bad, he’d buy 25 lobes of foie and tell us to send a foie course out to every guest for free. Or he’d buy $35,000 in black truffles and we’d have to learn how to preserve them because he wanted to serve them for six months.”

The Book

No one was forced to be in Charlie’s kitchen. Most came willingly because of the cookbook, the burgundy colored one. Trotter’s cookbooks sold well, but not like best-selling novels. They’re currently out of print.

They say that the Velvet Underground didn’t sell a lot of copies of their early records, but that everyone who did buy a copy started a band. The Trotter cookbook was a lot like that. It felt like everyone who bought one, either ended up in Charlie’s kitchen and/or started their own restaurant.

I moved to Chicago because of that book. I worked in Cleveland after graduating from college. Living on my own for the first time, I was mid-bite in the middle of my 500th Hot Pocket (ham and cheese), and thought, you need to either learn how to cook or accept you’re gonna die young from eating too much processed food.

I made fresh salsa. It kicked Pace’s ass. I made a steak. Then I made crème brulee. Then souffle. I watched Food Network like it was my job, back when Charlie’s good friend Emeril was king and they cooked for passion of craft, not competition. I started to dine out like it was my job, hitting Iron Chef Michael Symon’s Lola.

I read cookbooks during this period with the rapture one might reserve for a good murder mystery. I discovered the Trotter book at a Barnes and Noble in Cleveland Heights, Ohio. It hit me hard. The company I was working for had a branch in Chicago.

After reading Trotter’s book I told my bosses if they ever needed me to transfer to the Windy City I would leave immediately. A few months later they did. I accepted, not because I cared about the job, but because I had to dine at Charlie Trotter’s. I realize now I probably could just have bought a plane ticket to Chicago. It would have been much less life-upending.

That was the power of Trotter’s full-color close-up photography and his story of endless searches for novel ingredients, and pursuit of flavor fusions that actually worked: you had to have it now.

Not only did I move to eat at Charlie Trotter’s, but eating there made me a food writer. I wrote my first food review ever after dining at Trotter’s in an email to my friend Aamir.

I loved my meal, but I also made a mistake and evaluated Trotter without proper context. I failed to understand in that moment that Trotter’s work had created and inspired almost all of the competition I was comparing him to.

The review is the naïve ramblings of a financially-strapped twenty-something, but it did have an ironic line.

“ .. in some ways I think the expectations are so high when you come here that you think the experience will somehow change your life. I think it is hard to deliver on these type of expectations overall. Like I said, this kind of food is becoming more widely available. For what we spent at Trotters, we can go to Blackbird or Spring 4 times....it then becomes a question of value at some point. If you were infinitely rich, the innovation of Trotters is worth it on a regular basis, but I'm not sure we will go there again until we have exhausted a lot of other places. It also makes me rethink going to Trio or Tru, as they deliver a similar experience at similar cost. Tho, I hear that Grant Achatz or whoever at Trio is innovating in serious ways so that might be the draw.”

Achatz (or “whoever”, LOL) felt the same way I did about Trotter’s book, finding it on a shelf in a Borders in Grand Rapids, Michigan where he was working as a cook at a restaurant in the Amway Grand hotel. He still has the receipt from his purchase.

Charlie’s story in that cookbook and beyond is one of a human committed to doing something no one else in Chicago or America had, which meant building the most creative and best tasting menus in existence.

Achatz Working At Trotter’s

Moved by that, Achatz ended up writing at least “11 or 12” letters asking to work for Charlie. Trotter eventually left a message on Achatz’s answering machine saying that he was offering Grant an opportunity because he wanted to find out whether Achatz was crazy or really this dedicated.

When Achatz arrived, he got his first lesson in Trotter’s leadership. Charlie asked Achatz to introduce himself to the whole restaurant staff and tell them why he was there. Achatz said something about learning at the best restaurant in America. Trotter told him “That’s why everyone’s here. Tell me something original.”

People may not have been used to getting pushed this way, but this is what made the creativity of Trotter’s superlative. Still, the Trotter’s kitchen felt like the Hotel California, aka you can check out any time, but you can never leave. You could physically exit the restaurant, but a lot of people would still be psychologically chained to that Bonnet stove.

Achatz did split. He never felt like he was his best self at Trotter’s, making simple mistakes like plating on a dusty dish or refrigerating toasted nuts which made them soft and mushy. So he quit.

Charlie took in this news while standing against the side of his maroon Jaguar and told Achatz that he was basically dead if he left the restaurant before working there a full year.

Achatz went off to the French Laundry and a stint of winemaking in Napa Valley. When he left the Laundry to open Trio in Evanston, Achatz’s mentor chef Thomas Keller gave him the parting advice that, “Charlie is going to crush you.”

Trotter tried, calling Achatz work “nonsense on stilts” in the New York Times. Many people think that Achatz descended only from El Bulli and Ferran Adria, but what a lot of people don’t know is that the Trotter kitchen indirectly created some of the framework for Achatz’s success.

It did so by making Chicago a dining destination, by changing people’s attitudes about fixed menus, by encouraging and partnering with innovative purveyors like Tom Cornille, one of Chicago’s greatest produce guys (still a purveyor for the Alinea group) and farmer Lee Jones of The Chef’s Garden who produced microgreens, Charlie’s answer to Chez Panisse’s pervasive mesclun salad mix.

Matthias Merges, now of Billy Sunday and Mordecai, who has as much responsibility for the innovation and success at Trotter’s of anyone who wasn’t Trotter reached out to a guy named Philip Preston at Polyscience because he had cooking ideas that surpassed the capabilities of the kitchen tools he had at his disposal.

Merges collaborated on the creation of the first immersion circulator built for restaurant kitchens. Charlie Trotter’s was on the cutting edge of sous vide cooking. This led to Polyscience inventions like the smoking gun and the anti-griddle, all staples of Alinea. If what Achatz was doing was nonsense on stilts, Charlie Trotter’s restaurant built those stilts.

Enemies Become Friends

Achatz is an internally driven guy and a realist. He expected people to come for him, because he had studied history, and he knew people came for Charlie in the same way. He expected skepticism, but for Charlie to say the “nonsense” thing in the very public way that he did, Achatz told me it lit a real fire under him. Achatz said in the Love, Charlie documentary, “I didn’t know if we were friends or enemies.”

In the middle of his growing success at Alinea, Achatz publicly announced his battle with tongue cancer. Trotter invited Achatz to his house for a party via a hand-written snail-mailed note. In the middle of the party, Trotter gathered everyone and gave a passionate speech about Achatz and told the community they needed to rally around the chef.

Achatz success at Alinea came in the same way as Charlie’s. They both had a discipline to doing things that had never been done. It’s a very simple concept. Anyone can espouse it. Most do not because executing on that philosophy is a very lonely and hard road. It means working until four a.m. and coming back at ten in the morning the next day every single day. It means pushing teams beyond their perceived limits. It means refusing to do something until a new path shows itself.

Achatz the manager and leader of Chicago’s greatest dining destination, a spot once held by Trotter’s, now realized the toll it took to get to the top, and ultimately understood Charlie a lot better.

Achatz now knew why Trotter pushed the way he did, and Charlie eventually understood Achatz’s humanity and talent and honored that. In an era where everything feels extremely polarized the story of Achatz and Trotter is a beautiful shade of gray we could all use.

The Charlie Trotter Tribute

That’s why Achatz is devoting the next three months to creating an homage to Charlie Trotter at his Fulton Market restaurant Next. He said of the meal which runs through December, “For me it is the final punctuation on a very complicated relationship, so for me this is me saying to him, we’re good, we’re friends.”

The menu couldn’t come at a better time. Though it’s hard to believe for those of us who are passionate about culinary history and lived in a time when the restaurant was open, some cooks and diners in their twenties don’t know how important Trotter is. Even people in their thirties who work in the industry may know of Charlie, but they don’t really know his impact, even if what they’re doing is possible because of his work.

I asked Tentori if his younger cooks knew about Trotter.

He said, “At GT Fish I saw that a lot of them didn’t, so I took eight old menus, his chef’s coat, and matchbooks and had them framed. I hung it in the kitchen as a reminder.”

Dylan Trotter worked in the GT Prime kitchen for a while. I asked him if cooking with this monument to his dad next to him was daunting. He said it made him proud.

Even Next restaurant’s smart and incredibly-driven leaders executive chef Alan Mileykovsky and GM Kate Lang admitted they learned a lot more about Trotter while working with the Alinea group.

Lang, who also hails from Achatz’s home state of Michigan, said, “When I worked at Bar Takito, I didn’t know much about him. I learned about him through working in this restaurant group. …Other people my age, the [Alinea Group] business team, they’re doing the marketing and sometimes joke that they don’t know who he is and say, will anyone know?”

Mileykovsky, a devotee to eight string guitar and playing metal riffs on his Instagram in his spare time said, “I had a fine dining class teacher in culinary school who worked at Trotter’s, so I knew of him. I collect cookbooks, so when I got the Trotter one, I started watching YouTube videos and learning about him.”

Whatever Lang and Mileykovsky didn’t know, they became quick studies in the arduous process of preparing for what they call a Next “time capsule” menu.

Menu, Service, and Design Development for the Trotter Tribute

I visited Next a week or so before the Trotter dinners kicked off to see some of the development process and ask about the concept.

I asked Lang if they would adjust Next’s service at all to mirror more of the Trotter’s style.

She said, “Trotter didn’t do a lot of table-side service except shaving truffles, not even pouring things, so we might pare some of that back, but that’s one place where we’ll try to maintain our own identity.”

I wondered if they were recreating classic Trotter dishes, would they also be using modern vintages of the same documented wine pairings.

Lang said, “We want to honor his legacy of wine pairings and non-alcoholic offerings. We won’t do cocktails because he didn’t serve spirits. Charlie used a lot of classic producers. He leaned on America and France. We’ll dabble a little more internationally but focus on classic producers of high quality. We want to pair the food with things that make sense now and still honor that legacy.”

Achatz arrived in the Next basement prep kitchen in the middle of my conversation with Lang and Mileykovsky fresh off a call with NASA. He fist bumped Mileykovsky and said what do you think about “Next: NASA”?

Chef Alan responded, “You have always wanted to do a space menu!”

I don’t know if there’s freeze dried ice cream as designed by the Alinea group coming to Next in June 2025, but I sure hope so.

Achatz was here to see some of the memorabilia Dylan Trotter had sent over for the team to use as décor in the Next space during the Trotter menu run. This included original charger plates, magazine articles, old menus, a rich analog archive of Trotter history. There was even a framed menu and photo of a much younger Achatz cooking alongside a dream team of Adoni Aduriz of Mugaritz, Pierre Hermé, the macaron and pastry god, and Wylie Dufresne of the defunct WD-50 at Trotter’s.

The Next team secured a piece of granite to match the bar top from Trotter’s to refurb their own host station. They were also planning on adorning each table in the restaurant with Trotter-esque white bud vases and a white lily arrangement as Trotter preferred.

Achatz and Mileykovsky were making dish refinements based on a staff tasting of the Trotter menu earlier in the week. The Next team held five tastings and made adjustments after each one before delivering food and service for the Trotter tribute menu to the general public.

I asked Achatz earlier in the day what the execution focus would be. Was this menu an exact replication of Trotter’s, an homage, or something in-between?

The Next team would focus on some well documented dishes from the cookbook, but also from the period Achatz worked at the restaurant. Though they had the Trotter cookbooks as a guide, even those snapshots were fluid.

Mileykovsky said, “They changed the menu everyday, sometimes in the middle of service. If you look at it closely, some of the pictures of the final dishes in the cookbook don’t represent every component in the recipe, so there’s a lot of gray area.”

I asked Achatz whether the stakes were maybe a little higher for this tribute menu than others Next had done like Bobby Flay, who is a personal friend of his, or Julia Child who never ran a restaurant, because there are so many living Trotter alumni and diners who still remember the original.

Achatz acknowledged that he had reached out to some alumni to get their blessing. He also floated the idea of an alumni night where everyone associated with Charlie Trotter’s restaurant might all gather at the original space for a dinner put on by the Next crew. He said that this menu was probably the most daunting and that what was paramount is that it would be delicious.

Achatz, Mileykovsky and I tasted through some of the proposed dishes. A chilled heirloom tomato soup made with Froggy Meadow Farms Sungolds topped with quenelle of avocado coriander sorbet and finished with tiny brioche croutons looked a little like a deconstructed gazpacho. My 1990s cliché hackles went up. But the raging sweetness and acidity, the temperature contrast of the ice cold sorbet and the slightly room temp soup, and the crisp salty crouton textural accent made me realize few people cook like this anymore.

In a good restaurant you might get one or two opposites in texture, flavor, and temperature, but rarely all three on one plate at the same time unless you’re in Michelin-level territory. The crouton wasn’t in the original recipe, but the Next team added it as a refinement.

A rutabaga gnocchi plate came next. It had a trompe-l’oeil component, whereby some of the dumplings were actual gnocchi pasta and others were roast soft pieces of rutabaga that looked like gnocchi. It was delicious, but Achatz said, “This is kind of one tone.” The dish would be reserved as a back pocket dish to serve guests off-menu, but would not make the starting line-up.

A venison round perched on a silky oxtail rillette dripping in fiery mole was a banger. I loved it but asked Achatz if guests would complain about the heat level. He didn’t think they would.

A banana bread round oozing with chocolate ganache was crowned with a coconut tuile and malt ice cream. Little music-note like swooshes of ganache flanked the plate. Achatz noted the saucing as a little old school.

There was also a supplement dish of black truffle ice cream swimming in an orange sauce alongside toasted hazelnuts rained with what felt like a gram of black truffle. If you are on the fence about adding this to your meal if you dine at Next, just do it.

The chefs had sous-vided a poussin breast for another dish, but the recipe came from a time before sous-vide would have existed at Trotter’s. This kind of modern adjustment is the kind of subtle Alinea group spin you can expect on the Trotter’s menu.

Achatz pointed out how Trotter’s sauces were often more like a jus, loose and flowing, less tight and concentrated than they would be in a modern restaurant. I suggested it was kind of like a Rorschach inkblot in sauce form, exactly what you’d expect from a guy who loved free-form and improvisational jazz, the work of Miles Davis.

I asked Chef Alan what he had learned by spending so much time in the mind of Trotter, and he said, “Trotter took French foundations and twisted them by plating in a more mosaic style. His sauces are these delicate concentrated broths without creams and heavy demi-glace. He was one of the first people to really meld international flavors. All of this stuff shows up in what we do at Alinea group, but now we know where it comes from.”

The Trotter Friends and Family Dinner

I couldn’t stop thinking about the tomato soup, so I was glad to be back a week later at the friends and family preview dinner. The Next dining room had been transformed with all the memorabilia I’d seen in stacks in the basement prep kitchen. Miles Davis’ golden trumpet tone wove through the air. This was a slight departure from the original Trotter’s which only had speakers in the front bar, but not the main dining room, so people’s focus would be solely on the food.

Dylan Trotter told me that the music from the bar at Trotter’s often did bleed into the main dining room and then shared a fact I never heard before which is that at the end of service at Charlie Trotter’s they usually played Take Five by the Dave Brubeck Quartet.

I don’t know if the guy sitting next to me during dinner was Trotter’s former florist, but he knew an awful lot about the history of the Trotter flower arrangements, telling his dining companion that at one point Trotter preferred a white lily with red flecks, and that there was a period of Tiger Lilys followed by the pure white ones that also graced our table this evening at Next.

Dylan Trotter was also in the house. Some of Charlie Trotter’s old purveyors were also dining.

The sun gold soup was still a rager and unlike at Trotter’s was poured tableside.

The Venison mole was a little more muted. Dylan ate again on opening night and told me that the mole got punched up again.

The banana cake now had a swirl sauce pattern.

The Next crew was making constant adjustments.

The poussin was silky and bathed in black truffle stew. It was served with a 2019 Altesino Sangiovese Brunello di Montalcino. Sangiovese is probably my desert island red varietal of choice. Normally you wouldn’t serve a big red like this with chicken, but a big smoky note in the dish and the truffle waft worked well with the bold pour.

A lot of restaurants now serve a glass of wine that can bridge a few courses, but true to Trotter’s, every single dish at the Next Tribute got its own wine pairing.

My favorite dessert which I hadn’t eaten during the recipe development night was served on a gigantic whimsical Vista Alegre plate. It was Trotter’s homage to another culinary legend, Nancy Silverton, a pannacotta from her La Brea bakery/Campanile days.

Silverton’s version was originally made with a vanilla tuile, but the Trotter version served at Next sat on a bed of puff pastry. Whereas Trotter’s original custard was flanked by free form dried fruit, the Next version included a series of precise wafer-thin oven-dried cross sections of strawberry, pineapple, and fig.

This dessert was paired with 2013 Diznoko Tokaj Aszy 5 Puttonyos Tokaj. Though everyone serves Tokaj now, back in the early nineties sauternes was the dessert wine rage. Trotter’s restaurant was one of the first spots to popularize Tokaj as an alternate sweets pairing.

Chef Tentori ate the Next Trotter’s meal the night after me. I asked him how the experience was for someone so intimately connected to the original kitchen. He said, “To be honest I didn’t know what to expect. I know that this team can do the service and the wine and the ambiance, but the food at Trotter’s was so specific. Their [Next’s] style is so much different, so I didn’t expect to see all the foams, the juices, the right spices. They even got the level of luxury ingredients right. I was so happy.”

He added, “What we did at Trotter’s sometimes, especially now, looks easy, but it was incredibly specific and hard to do. I think there’s a lot of people who want to taste what Charlie Trotter food was like, and now they can because Achatz and his team really nailed it.”

As someone who ate at the original Trotter’s I agree with Tentori. Eating this meal at Next felt like sidling up into a comfy chair and dropping the needle on a classic side of vinyl. If you never ate at Trotter’s or you’re younger it might feel like discovering Bob Dylan’s Blood on the Tracks for the first time on Spotify. The food is not of this time, but the flavors and style persist with undeniable appeal.

I used to eat at Next a lot, but I hadn’t been here in a very long time, partially because they always take care of me as a VIP guest and I’ve never been comfortable with special treatment of any kind. I probably need therapy for that.

But, the downside of being away for so long is I’d forgotten how warm, knowledgeable and approachable Alinea Group service is. You want to go deep on wine knowledge? No problem. You want to talk about Chappell Roan’s Pink Pony Club? They can do that too. They meet you at the level you’re at with a joyful enthusiasm that’s very rare anywhere.

Speaking of joyful enthusiasm I promised you a flying chef.

My belief of great chefs is that they have a certain combination of characteristics that would make them great at whatever they chose to do. Before he was a cook, Trotter dedicated himself to gymnastics and was incredibly athletic. That’s why it was no sweat for him to do that trampoline photo. One night many years ago, Dylan told me that his dad had topped that photo in a more fantastic way.

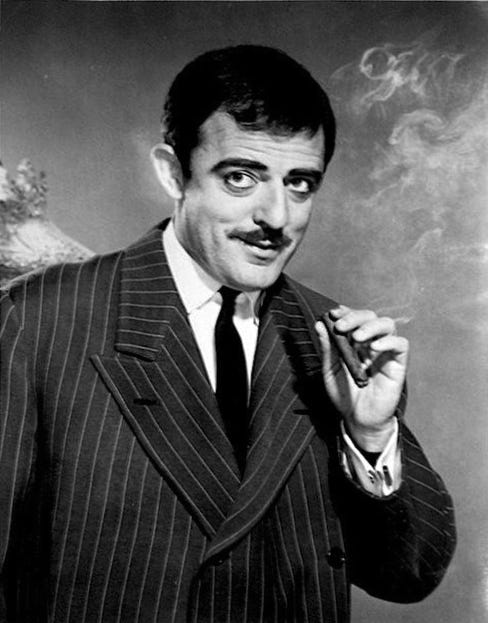

John Astin once sat at the Trotter’s bar. You might not know him, but he was a fantastic actor, probably most famous for playing Gomez Addams (he’s also Sean Astin’s, aka Samwise Gangee in Lord of the Rings, dad) in the original television version of the Addams Family.

If you’re younger and reading this you probably know about Wednesday on Netflix with Jenna Ortega, or at least you’ve seen the famous meme dance scene. Well, there’s no way they make that Netflix show if the original version led by Astin wasn’t mesmerizing for an earlier generation. Astin’s charm then was Ryan Reynolds/Ryan Gosling level.

Anyways, Astin was drinking at the bar and chef Trotter rolled up and said, “Sir, you entertained me so much as a kid, I’d love to entertain you.”

Trotter climbed up on the granite bar top in his chef whites, summoned his gymnastics training and performed a full back flip in front of the actor. I have no doubts that wherever he is now, Charlie is somehow still flying.

Next is located at 952 W. Fulton Market in Chicago. The Charlie Trotter menu runs through December 31, 2024.

__

I contributed to the Alinea cookbook. I still receive royalties for it. I am not anonymous when I dine at their restaurants. While I always pay my own way for review meals, I attended the Trotter friends and family meal for free, a rare exception, because I was not writing a review, but writing a feature story. What does this mean? Hopefully nothing. But, it’s always good for the reader to know the context a writer is working within.

What a terrific report. Thank you.

Michael, we dined at Charlie Trotter’s just once. Thank you for invoking the memories and celebrating the Alinea Group and the Next team’s homage.