What happens when you meet your gods and they reveal as mortals?

In that moment you are given the most extraordinary gift, nothing less than the secret of life. That’s what happened to me when I spent ten hours observing one of Chicago’s most legendary restaurants about three weeks ago.

And that’s all we’re really doing here anyway, searching for the answer. When I write of food, it is only as a conduit for identifying meaning.

One of the reasons I ended up choosing restaurants as my prism for understanding the world was because of the appealing mythology of the unbridled creativity and constancy toward perfection presented by Charlie Trotter. The thickly bound, shiny, full bleed photography-filled Trotter cookbooks put together by Charlie and his team were a talisman.

Because my culinary skills at the turn of the 2000s were mostly confined to pulling the pre-serrated opening on a box of ham and cheddar Hot Pockets, the Trotter recipes read to me like the lyrics to The Beatles’ Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds.

Even if I didn’t understand them, I wanted to picture myself on a boat on a river with tangerine trees and marmalade skies, or in this case floating in a burgundy-soaked raft of poached pear larded with clouds of piped spice cream.

I did then and I still do now. Charlie played the piping bag and, I, a native Michigander, then living in Cleveland, scurried like a marvelous mouse to this swine slayer of a town, settling here for what I believe will be the rest of my life.

One of the first things I did, even before all the moving boxes were unpacked, was dine at Trotters. I was too young and the hospitality then was not like it is now, where you meet your guests where THEY are. Back then it was more about judging the diner by the size of the wallet. No one was mean, but my expectations suffered in the moment of reality.

Other restaurants filled in for that lack, Blackbird and Paul Kahan, foremost. And I was on my way. I wrote and I podcasted (in 2005, LOL). I latched my wagon to the newest demigod, then Trotter’s foil, Grant Achatz, and worked on the Alinea restaurant cookbook.

I met Emeril. I met Anthony Bourdain and we used to exchange DMs. Despite all this I could never bring myself to reach out to Trotter. A mix of fear and reverence held me back.

I finally spoke to Charlie in 2011 at an open forum. For a guy who lived and died by what was wrought by his chef knife and acidic wit, a particular cleaver had fallen hard in the middle of his back. Michelin, a guide which would never have visited our little hog hamlet without the work of Charlie, had arrived and granted only one star to the king.

By then, I’d heard the stories of Trotter’s relentless obsession with success and perfection. I’d asked him, “Did you expect more stars?” The truth is, we never really talked, because he just looked at me like he was channeling a Darth Vader-like-form of The Force that never came. I have no doubts he was wringing my neck in his mind’s eye. He then turned to a group of other journalists and asked if anyone else had any questions that weren’t about the Michelin guide.

I wasn’t trying to be a dick. I was searching for meaning. How does one of the greatest to ever do it in Chicago and frankly in America not get three stars? It was inconceivable, like reading for the first time that Paul McCartney couldn’t read or write music.

I believe Charlie didn’t answer my question because he couldn’t. He felt the same way I did, and spent the next couple years after closing his restaurant obsessed with finding the reasons for his denial until he passed away at age 54.

What hope was there for any of us if the G.O.A.T. went out like that?

It's better to have loved and lost, right? Maybe not, because now I think I’ve learned it’s better not be loved at all. Well, that’s not entirely right, rather it’s better not be loved by the gaze that doesn’t matter, but the one that does.

Frankly, if you’ve read this far, one of your criticisms is probably, Mike, why are you deifying chefs like a BTS fanboy?

And you’re right. I know this because I finally saw something that really made me understand what I inherently knew, sometimes bought, but ultimately ignored far too much. The acclaim doesn’t matter. Only the work does.

The opportunity to experience this revelation happened when a few folks tipped me off to the fact that Roland Liccioni, chef of Les Nomades was retiring on Friday, March 22, 2024.

Some of you are like Roland who?

And let me tell you, that’s the damn secret right there.

But before we get to that, even if you’re a student of Chicago culinary history, how far do you really go back? Do you know of Charles Rector and his oyster house or Chin Foin and his Chinese restaurant empire built when the city was still a swamp, its wooden houses fine kindling waiting to be consumed by the great fire?

Or do you have more of a recency bias?

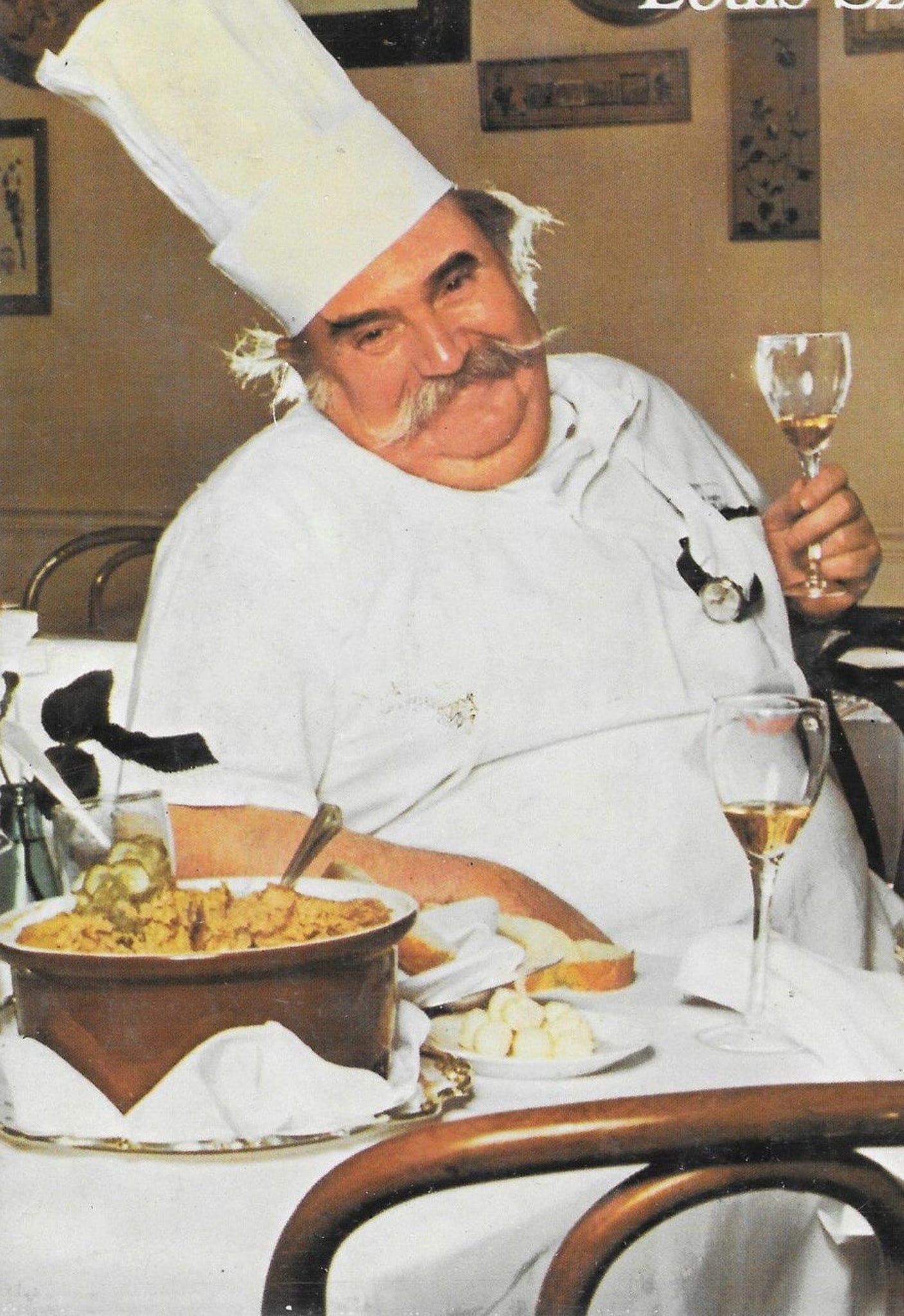

Arguably the first real “celebrity” Chicago chef was Louis Szathmary of The Bakery in the 1960s, notably, the writer Nelson Algren’s favorite cook.

A little after Louis there was a guy named Jean Banchet who opened a spot called Le Francais in 1973 which made Wheeling, not Chicago, the center of the American culinary universe.

Back in the city, Jovan Trboyevic made waves at a place called La Perroquet. He left that spot to open a private dining club in a magnificently hushed brownstone just a half block from the raucous bustle of the Magnificent Mile, called Les Nomades in 1978.

Ina Pinkney, proprietor of the defunct Ina’s and Chicago’s famous breakfast queen said, “Bill, my husband had set up a standing weekly lunch date for me at Le Perroquet. It was so lovely. Jovan was so lovely. One day he asked us if we wanted to join this private club he was opening called Les Nomades. Dues were $1. Of course, we said yes.”

Pinkney added, “Bill and I were an interracial couple, and we were not welcomed everywhere. But we always felt welcomed with Jovan. One night this guy started approaching and Jovan just stood between us and used his arms to shield the table.”

Trboyevic was old school. While the Pump Room in those days was a place where everyone mingled, no doubt trying to elbow in to see what celebrities were holding court at booth one, Les Nomades had a strict no table-hopping rule. You did not approach other diners or hang out, even if your best friend happened to be across the room. Men had to wear jackets. In 2024 at Les Nomades, they still do.

Pinkney said, “Jovan had this huge zinc bar at Les Nomades, it took up the entire room. One day we came for dinner, and there was only a piece of it left as a service bar. We asked Jovan about it and he sighed and said he sold it because, the heathens (local diners) don’t understand a zinc bar.”

While Jovan was doing his thing at Les Nomades, a 14 year old Vietnamese Corsican living in Biarritz, a budding soccer talent named Roland Liccioni, inspired by his favored French teams Saint-Germain and Saint Etienne, was deciding whether he should be a professional footballer.

When Roland asked his father, an accountant for the French army, for advice, his dad didn’t try to influence him either way. He just told Roland he had to really think about it.

Roland reasoned that a footballer’s career would be over by 28 or 29, so in 1970, he enrolled at the Ecole Hoteliers de Biarritz. He studied for three years, graduating first in his class which earned him a spot in the kitchen at the Paris brasserie Bofinger.

Bofinger was not any Brasserie. Founded in 1864, some believe it was THE first brasserie in Paris. Whether true or not, it was, not unlike Charlie Trotter’s, the place every celebrity, artist and prime minister needed to dine. François Mitterrand celebrated his election to the French presidency here.

Roland said, “I cooked for everyone, artists, actors, you name it. [Salvador] Dali ate there.” Roland’s early experience set a tone that defined the rest of his cooking life. Roland who would cook regularly for Chicago Bulls like Bill Cartwright and Scottie Pippen at Le Francais or actors like Jack Nicholson and James Garner was never intimidated by the brightest of lights.

In 1991 Roland was asked to cook for Jean Banchet’s fiftieth birthday, an affair attended by Paul Bocuse, Joel Robuchon, Andre Soltner, and a bunch of other very famous French demi-gods he’d never met. I asked him if he’d been nervous. He looked at me as if I’d asked him something stupid like whether he loved his children and very casually, said, “No.”

Uneducated diners you can fool, but these guys knew where all the dead bodies were buried and they had a constellation of Michelin stars between them. Success at something like this is not a given no matter how talented you are.

In 2007, Charlie Trotter brought Thomas Keller, Ferran Adria, Heston Blumenthal and Wylie Dufresne into Schwa, to witness the work of a budding star named Michael Carlson. By all accounts Carlson slayed that night, but it also sent him off on three-day drug and alcohol-fueled bender which ended up with him closing the restaurant for a short time.

Of Roland’s dinner with the French titans, I asked him if he was relieved. He shrugged and said, “I think it went well. They all told me to come visit them when I was in France.”

After Bofinger, where his bosses begged him not to leave, he moved to London in 1980 to work for Albert and Michel Roux at La Gavroche who were pioneering “nouvelle” cuisine, eschewing heavy creams and butter in favor or pure flavor through sauce reductions in the UK the same way that Michel Guerard and Paul Bocuse were in France.

Roland led the kitchen of 25 within three months. By 1980 Carlos Nieto, the maître d’ at Le Francais was looking for a chef to head his forthcoming restaurant in Highwood, Illinois.

Once again Roland’s bosses did not want him to leave, but the 25-year-old wanted to see more of the world, and he left to helm the kitchen at Carlos.

A young Charlie Trotter fell in love with Roland’s work there. Roland was one of Trotter’s early heroes and his son Dylan recently told me his dad believed Roland was one of the most creative chefs he’d known.

Charlie repaid that creativity by hiring one of Roland’s best young cooks, Guillermo Tellez, one of the early backbones of Charlie Trotters who now runs the excellent farm to table restaurant Flora Farms in Los Cabos.

I asked Roland if Trotter had poached Tellez. Roland said, “Yes. But it’s ok. I remembered how my bosses never wanted to let me go, so I’ve always told my cooks, they’re free to go wherever they want. I just tell them, they better go somewhere where they can learn.”

At Carlos Roland got four stars. In 1988 Banchet decided to lease Le Francais to Roland and his then wife Mary Beth. Most of the Chicago culinary world told the pair they’d fail. After a few months, some writers and chefs believed Le Francais was even better than before. It was certainly regarded as the best restaurant in America at some point under their leadership.

Roland and Mary Beth got four stars again. Despite this success, Roland still had not won a James Beard “best chef” award, a glittery accolade desired by very serious chefs, in the mid-1990s.

Charlie Trotter, who believed it would help Liccioni’s candidacy, kept asking Roland to cook a dinner at the Beard House in New York. Roland kept saying he was “too busy”.

Already in his forties, a time when most executive chefs cede daily cooking to their team and spend most of their time managing the business, Roland was “too busy” because he was getting up at 5 a.m. every day to go the South Water Market in Pilsen to select produce and he was still cooking on the line.

Evan DeVries midwestern sales manager for La Colombe coffee who worked as a pastry chef under Roland said, “He’s as real as they get. The only time he ever missed a service was to attend another cook’s wedding.”

Despite not playing the game, in 1997, Liccioni was named James Beard Best Chef Midwest in a tie with Gabino Sotelino of Ambria. In a very rare moment of non-humility Roland told me, “The tie was political. I wish I didn’t care. Gabino is a friend and he knows I felt this way.” I asked him what he meant by that and he said, “He worked for a big restaurant group (Lettuce Entertain You) and they had a lot of pull.”

In 2000, Mary Beth took over Les Nomades from Trboyevic and Roland helmed the kitchen. The two ended up divorcing a few years later. Roland worked on a series of projects including Le Lan, Old Town Brasserie, and Miramar.

In 2011 despite their personal differences, Mary Beth hired Roland to take over the kitchen again. I asked her about this decision and she told me, “Well, I never worry about the kitchen when Roland is running it.”

Like Bofinger, Les Nomades was a place for Chicagoans of note. Roland said, “Mayor Daley and his wife Maggie, they loved Les Nomades. One night during the foie gras ban, Richard came in. I told him, we need it [Foie] back. He said, ‘Roland, I’ll take care of it.’ Three months later, the ban was over.”

During Roland’s time at Les Nomades he achieved four stars twice from the Tribune’s Phil Vettel. Based on all the articles I read written by Vettel, I believe Liccioni was the venerable critic’s favorite chef.

Roland was a hero of Charlie Trotters. He succeeded and maybe surpassed Banchet’s quality at Le Francais, and did something no one in the history of Chicago restaurants has ever done, which is earn four stars five separate times from the Chicago Tribune from three different critics.

I asked Roland if that meant anything. Returning to his usual self-effacing manner, he said, “No. It’s fine. Doing the work is what’s important.”

Despite this local acclaim, Les Nomades holds no Michelin stars, which I found kind of baffling. I asked him if this bothered him.

“No.”

While it didn’t get to Roland, it was something that bothered Donnie Madia, partner in One Off Hospitality (Avec, Big Star, Blackbird etc.) who told me, “Both he and Mary Beth are unassuming and unsung heroes. I don’t understand why they don’t have a Michelin star.”

Michelin star or not, about three months ago, Roland told his team that he was retiring and his last day would be Friday, March 22, 2024. This was not selected to honor some auspicious occasion. He chose it because his five-year-old daughter Grace was on spring break. He wanted to visit his wife’s family in China to see the spring blossoms.

Roland’s matter of factness I believe comes from the fact that he was the sixth-born in a family of nine brothers and six sisters. There was no place to be special. You put your head down. Roland helped his mother in the kitchen of her Vietnamese restaurant when he was young. He understood early that hard work was the reward.

Though Roland didn’t make a big announcement about walking away, word got out amongst restaurant vets.

Ethan Lim of Hermosa visited the last week for dinner and called it a “magical evening”.

Madia visited a few weeks before Roland’s retirement as part of a contingent organized by DeVries that included his partners Paul Kahan and Greg Wade of Publican Quality Baking, and Joe Frillman of Daisies.

Madia said, “One night I’m at Big Star. Trotter comes in. He gets up in my face like he does and says I’m closing. I knew I needed to go there one last time, but for whatever reason I just didn’t go. I was pissed then and now I’m even more pissed. I wasn’t gonna let that happen again by missing Roland.”

Of that night Frillman also told me, “It was exactly what I was hoping for. Old school, technically masterful and just what you don’t see very often these days. A true craftsman.”

DeVries concurred with this saying, “It was a very special night. That croque monsieur. Man. Even Paul Kahan had a tear coming down his face.”

Frillman added, “[Roland’s] a true chef’s chef. I had never met him prior to eating there and I have known so many people whose career he has touched and been a part of that and had heard the legend of Roland so much that it was pretty amazing to see.”

Despite all the restaurant people paying their respects, no one in the media was talking about this. Charlie Trotter’s hero, a king of kings was hanging it up and no one was gonna tell this story.

I knew I had to be in that kitchen on Roland’s last night. I reached out to Donald Young of Duck Sel. Roland had been his mentor, the guy who transformed Young from a wallet-chain wearing metal-head to one of Chicago’s premier young chefs. I asked him to ask Roland if I could hang out during Roland’s last night in the kitchen.

Roland said yes as long as “he [me] stays out of the way.”

I took a vacation day from my “real” job for the occasion. And then a couple days before the event, the bile rose in my throat. As we’ve established, my reverence for Trotter kept me away from him for a long time. Though I’d been writing for almost twenty years and though I knew I had to witness Roland’s retirement, I started freaking out. I thought about calling it off. I was like this dude is not gonna want me there.

I compensated for the fear by reading hundreds of articles about Roland, pretty much everything published since 1984. The more I discovered, the more the terror grew. I was a scribe punk about to besmirch a real palace with my selfish need to witness greatness one last time.

I’d told Roland I wanted to be there from the moment he arrived until the moment he left. I wasn’t even sure he understood what I was hoping for. What if he thought this was just an interview and he was gonna send me on my way?

But Friday morning came and I put my big boy pants on and arrived a few minutes before noon.

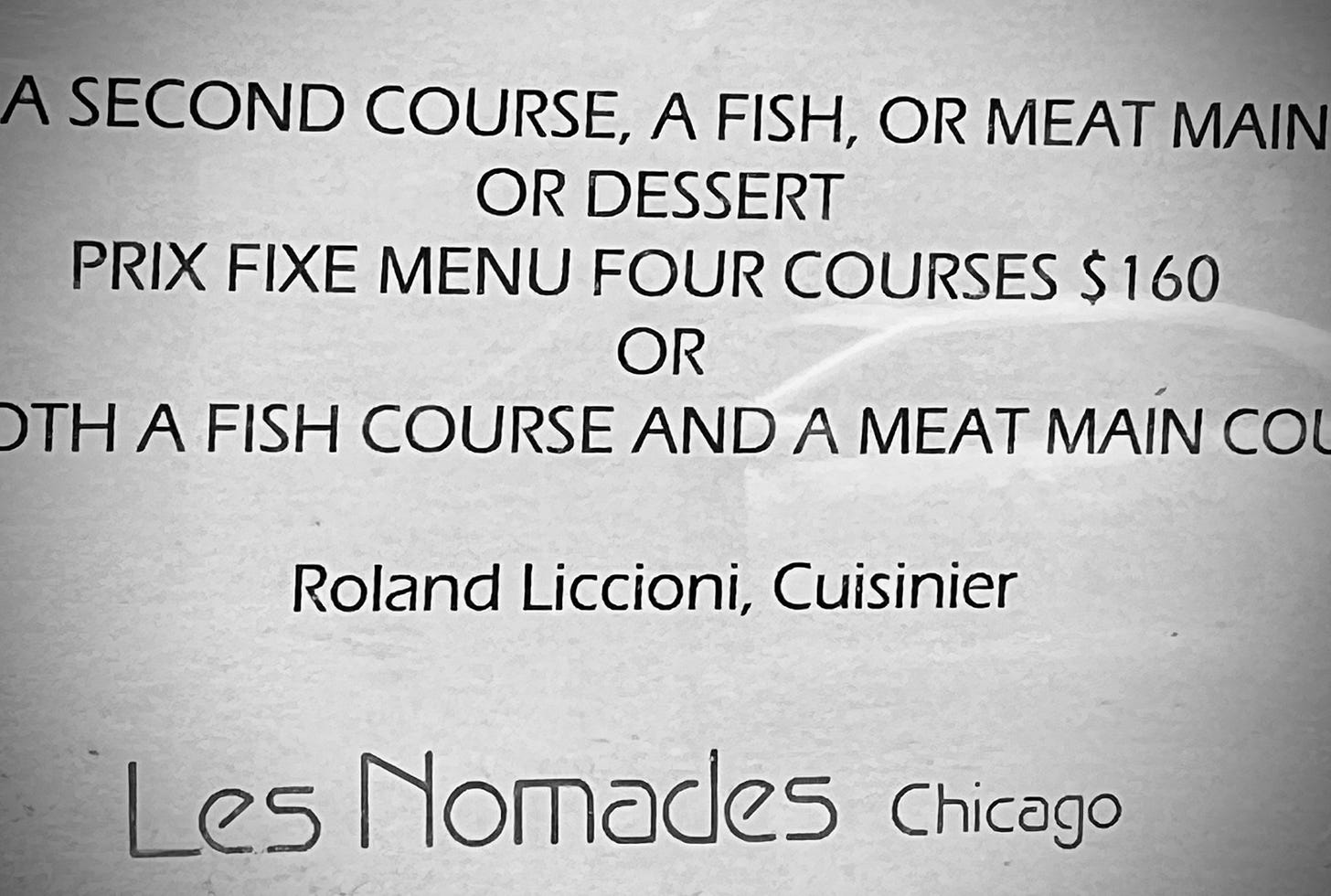

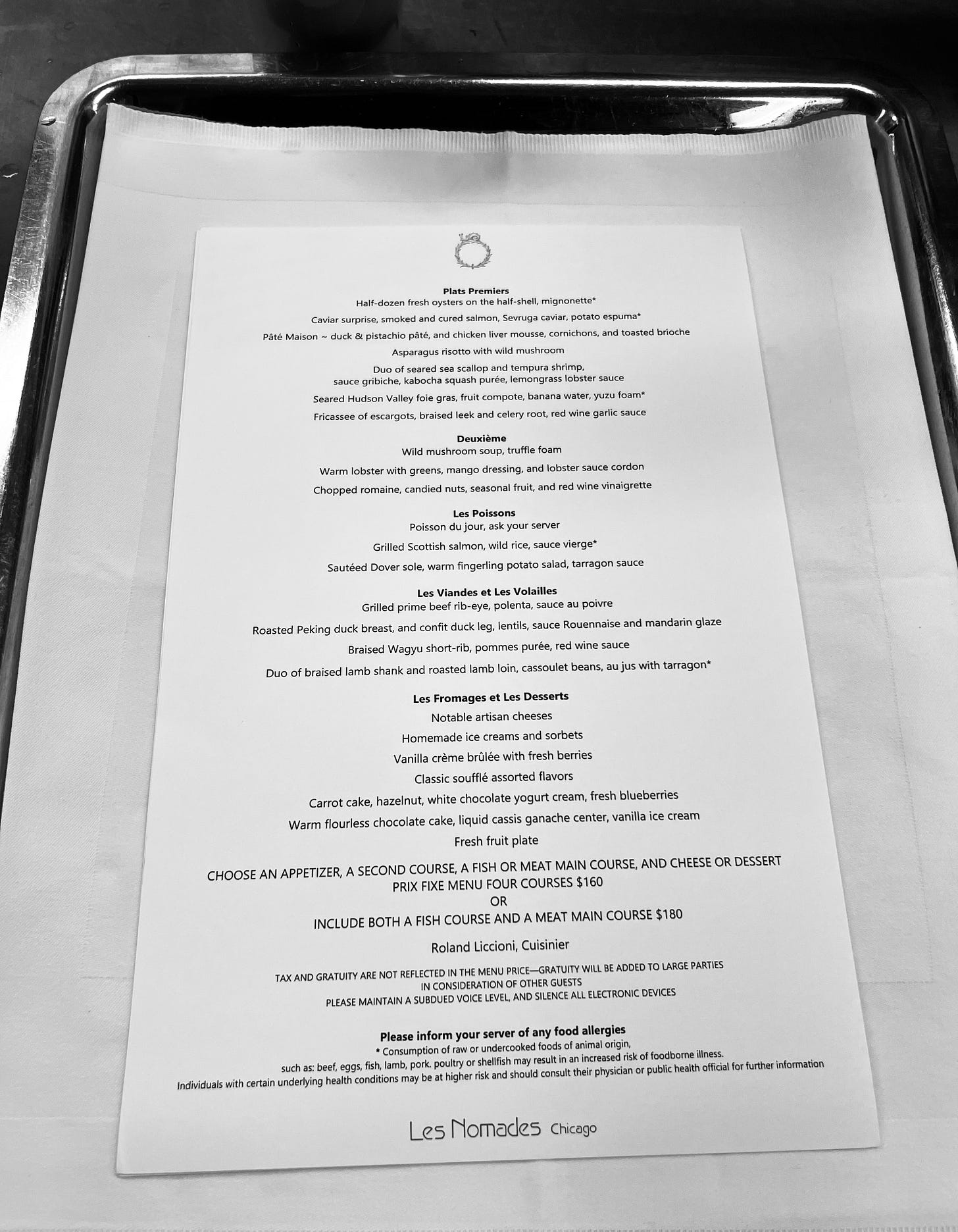

The gate was open. The daily menu had been posted. At the bottom it said, “Roland Liccioni, Cuisinier”.

OMG, the dude is so transcendent, he’s not even a chef. He a fucking cuisinier!

My French is not good. Those who truly understand the language will realize that “cuisinier” is the word for “cook”. 55 years in the kitchen and Liccioni saw himself as nothing more than a cook.

Staring up at the façade tucked away off Ontario, Les Nomades could be haunted. It’s got that feel. My colleague Mike Gebert of Fooditor recently wrote that it’s a little like the Overlook Hotel from Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining.

The landscaping alone, a bevy of short pines and smooth gray rocks, probably cost more than some modern restaurant’s linen budgets.

I walked up to the front, saw the jackets required plaque and was relieved that I’d chosen to wear one for this gig.

12:00 p.m.

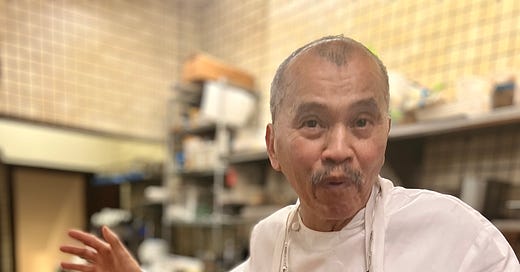

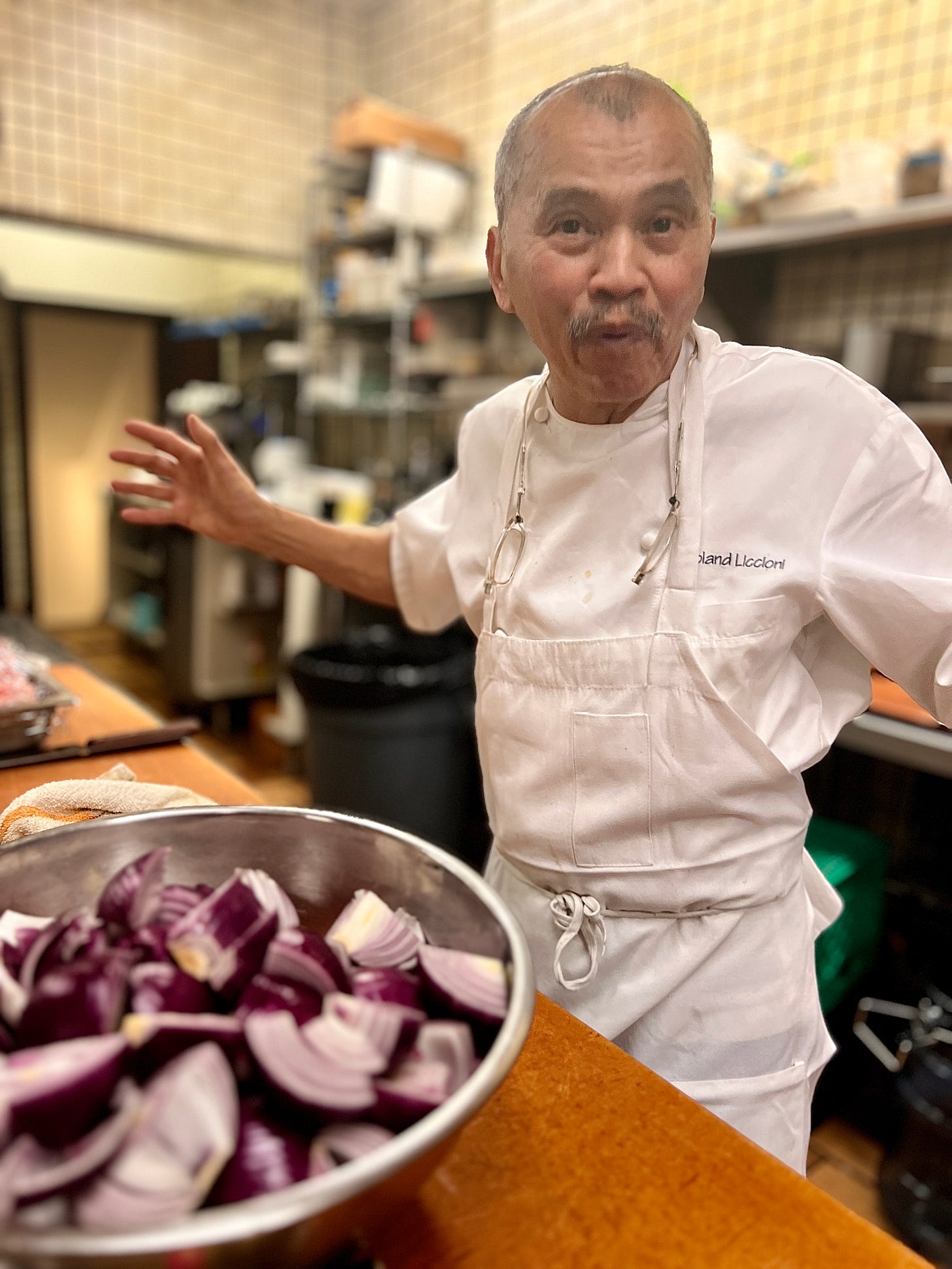

A copy of the print version of the New York Times lay on the Les Nomades doorstep. I knocked on the door and Roland answered. I’d seen many pictures of a young Roland, his jet-black forelock and pencil-thin mustache projecting a sort of mesmerizing power, and here he was now, a little more lined, a little salt and pepper sprinkled throughout. He wasn’t soft. He was lean. His forearms were sinewy. He was just different than I expected.

I assumed maybe Roland and I would hang out in the dining room for a bit while a team of chefs did the hard work in the background.

I thought maybe at the end of the night Roland and I would sit down over a glass of wine and he’d wax nostalgic about a long life in the kitchen.

None of these things would be unfounded based on my previous reporting experiences. When I interviewed chef Gabino Sotelino before the closing of Ambria in 2007, his eyes got a little misty recalling how he’d sacrificed so much that he’d missed his kids’ graduations.

I certainly did not expect Roland to be actively running the entire show. Most modern head chefs are at best expediting during service and certainly not working the line.

This is not a judgement of modern chefs either. A restaurant kitchen even in its most ergonomic form is brutal. Frillman has arthritis in both his wrists. Meg Galus of Good Ambler told me she wears compression socks, lidocaine patches, orthopedic inserts, and uses “so many stretching apparatus” to stay limber on her feet all day.

I’m in my forties. I stood in the Les Nomades kitchen for over ten hours this day. If I had to return for a second shift, my aching lumbar would absolutely have called in sick.

Roland quickly turned and headed back to the kitchen like some kind of 69-year-old Usain Bolt. I had to skip to keep up. There were no glasses of wine, just a huge carbon steel sauté pan piled high with mirepoix and lamb bones and a rondeau bubbling away with lobster parts.

Roland was alone. He’d already been at it for an hour. Before that he’d been at the market, which included a pick-up of Trader Joe’s peas.

What? I tasted them later during a family meal in a risotto. They were glorious. This was not some kind of grocery store compromise.

Surely, Roland was not also making sauces for tonight.

He was, but also because he knew he was leaving on spring break, he was preparing for next week too.

While Roland was retiring from daily service after this night, he revealed he was still planning on making sauces and stocks for Les Nomades part time, working a few shifts at his friend Joel Reno’s place in River North, Pistores, actively gardening more (DeVries told me Roland is probably responsible for growing the squash blossoms served in a hundred Chicago kitchens), and playing tennis.

Most importantly Roland was planning on spending more time with his family, and his daughter Grace, who recently received a toy kitchen wherein she cooks her accomplished father play food regularly.

Incredulous, I said, “You still make the sauces?”

He said, “Yes. Of course. I still work the line too.”

Me, “What?”

Him, “You’ll see.”

The benefit of reporting on a kitchen like this is I always pick up tips that make me a better home cook. Watching Roland, I learned so much that I’d never seen before that I felt I could almost run my own restaurant.

Liccioni layers his mirepoix, adding garlic and celery after the carrot and onion because the pieces are smaller and cook in less time. It also prevents them from getting bitter.

This is supposed to be an old school French-influenced kitchen, but very little butter is used. The nouvelle aesthetic is strong. Thickness of sauces is achieved through reductions and distillation. Demi-glace or the thick meat stock foundation, a powder-keg of flavor in a tablespoon, is made not with traditional veal bones, but unroasted lamb bones which have a roasty and sweet nuanced quality that veal does not.

It's not all classic French technique either. Liccioni gestured to a sous vide machine and said “You know what that is?”

I did, because I have one at home I never use. Roland was one of the first to sous vide cook in Chicago at Le Francais. He says a particularly “nasty” Wheeling health inspector told him it wasn’t safe, so he let the guy take some of his sous vide cooked proteins to study. The inspector came back and deemed them ok.

I was also surprised to see Roland using xanthan gum to thicken a lobster sauce. He said, “This guy working at El Bulli comes to stage and he sees me using this and says is that agar agar or what? I tell him. He takes the technique back with him.”

I don’t have Ferran Adria in my cell phone contacts, so it’s pretty hard to verify this, but I’ll take it on faith because so far nothing I’ve seen has suggested Roland is a fabulist. He’s also clearly, despite his traditional foundation, a dabbler in modernism.

12:30 p.m.

And then there’s the foie gras trick.

If you’ve ever made it at home, you know the duck liver is often still filled with residual blood and vascular remnants. All the books say you should use a paring knife to remove these. I’ve done this. It took me like an hour and resulted in melted foie and a butchered mass of wasted liver.

Roland slices his foie like bread and then literally blows the remnants out like he’s a human can of compressed air. I know what you’re thinking, especially after you see this video.

It’s a little old school, sure, but if you know how the science of a very hot pan works, it’s not unsanitary. More importantly it’s efficient.

1:00 p.m.

I ask if Roland knows who the new chef will be and, on cue, his sous chef Jack Brocar, a Chicago native and Kendall College graduate walks in the door.

I recognize this story is no longer exclusively about Roland. It’s about Les Nomades. Restaurants are a team sport. Though the media will tell you otherwise, and I’m guilty as hell on this count, it’s not a head chef-only affair.

Brocar is 27, but where most cooks his age have probably been in a handful of spots and stay for a year max and leave, he’s been here for seven already, not unlike Donald Young who did a similar stint.

Brocar’s neighbor was Michel Coatrieux, Kendall College’s dean of culinary operations, a schoolmate of Roland’s in Biarritz. Coatrieux, who also sent DeVries to work with Liccioni hooked up Brocar too.

Brocar said, “I came here and saw chef and this kitchen and it looked straight out of Ratatouille, and I loved it.”

I pressed Brocar again a week later and said, why did you stay so long though when most of your peers move so much, and he said, “I think I’m just an old soul drawn here like Jack Torrance to the Overlook Hotel.”

1:30 p.m.

Brocar’s old soul is making mango vinaigrette with sherry vinegar in a white Vitamix 5000 blender for probably the thousandth time.

Joel Reno walks in. He wants to wish his mentor good luck, but also needs to get some of Roland’s lamb stock for some of the dishes on his menu at Pistores.

Reno tells me, “I learned about the business side from [Jean] Joho at Everest, and the work from Roland. Just watching him, how he’s still on the line, his energy. He plays soccer and tennis still. No one makes sauces like he does. It inspires me.”

Roland breaks down a side of ribeye full of connective tissue topped with a massive fat cap. It takes him like five minutes. I ask him about the next generation of cooks and what he thinks. He tells me about a stage he had from Smith & Wollensky that didn’t know how to break down a prime ribeye.

I tell Roland a story about how Curtis Duffy of Ever told me none of his cooks know how to truss a chicken anymore. He nods in understanding and says, “All I want to do is share my knowledge. I keep waiting for young cooks to come here and ask. Some do, and some of them take a while to figure it out. Sometimes it just clicks. But, I’m still waiting for more of them. I don’t know what will happen to this industry.”

2:00 p.m.

Mary Beth walks in to the kitchen in a black tracksuit. Though she appears in this moment like the fifth unknown blonde member of The Beastie Boys, I am absolutely gobsmacked to meet her. Like Roland, she’s a stoic exemplar leader. She gets shit done.

Pinkney said, “I learned how to run the front of the house by watching Mary Beth. She taught me I have two jobs, fill the place up, and to metabolize anxiety of the diners so that you didn’t know the cooler wasn’t working. I have to project that everything is absolutely perfect so your dining experience is going to be perfect.”

Mary Beth’s been at the top of her game as long as Roland. I ask her if she’s worried about him leaving. She said, “I always worry when he’s not in the kitchen. He’s the best.”

Of Mary Beth, Madia tells me, “This [running front of the house] is what I do, so I’m paying attention to everything. There’s mohair on the seats. It’s all so elegant. And there’s this little zinc bar. There are only two things you can do with a bar like that, let it age and patina, or shine it every day for like 30 years. That bar is as shiny as the day it was installed. That’s all you need to know about the tone Mary Beth sets.”

Most of the rest of the kitchen staff has arrived. This is not a typical kitchen full of culinary school grads and sleeve-tattooed pirates. There are at least 150 years of culinary experience in the back of the Les Nomades house.

Juan Lopez, aka “Juanito”, has been with Roland for over 20 years. He spent a few more years before that at Charlie Trotters. The same goes for food runners Selvyn Depaz and Gilmar Gramajo, also former Trotter vets. They’re all wearing casual street clothes.

A lean tall black kid with high cheekbones that looks like a model walks in. I introduce myself and he stares at me. Roland steps in and asks me if I speak French and informs me that his garde manger cook Bakou Danfakha is a refugee from Senegal and he only speaks French. I would say je suis desole for assuming he spoke English, but I had to look that up just now. I’m an idiot, only capable of understanding some menu French.

This is not an issue for Roland. A lot of cooks speak kitchen Spanish as in “mueve to culo” (move your ass) or “caliente” as in hot pan coming by. Roland is fluent in English, French, Spanish and Vietnamese. He switches between French and Spanish and English all night long.

3:30 p.m.

There’s not a lot of talk, nor are there punch lists. Every kitchen I’ve ever watched has a walk-in or a pass plastered with lists of every task that needs to get done before service.

Even the Alinea kitchen, famous for its hushed balletic movements, looks a little like Ms. Sandy’s Dance School vs the Bolshoi of Les Nomades. Most of this crew has worked together for almost a decade.

Macho Alvarez, the vegetable cook is embedding carrots inside hollowed out zucchini and carving what look like asterisks out of yellow pepper making garnish for a duo of braised lamb shank and roasted lamb loin.

Roland likes to serve “duos” of things, different approaches to the same animal or vegetable to capture a diner’s interest with contrast.

Brocar doesn’t have to look at the clock to know it’s “comida” or family meal-time. He just starts handing out cans of lime LaCroix to the team and opening up hotel pans for family meal.

Roland and I took the meal, striped bass, pea risotto and broccolini, in the first-floor salon so I could interview him a little more.

There was bread, and a side plate of what looked like fluted meringues. I picked one up with my fingers only to discover it was butter. I’m sure Roland was like why have I granted this idiot access to my kitchen, but he didn’t let on. Instead, he continued his self-deprecation.

Have you thought about what your long career means?

“No.”

Were you nervous on your first day in a professional kitchen at Bofinger?

“No. I’d been at school for three years. I felt prepared.”

What was your plan?

“No plan. Just cook.”

Have you thought about what this last day means?

“Not really. I just want to go on spring break with my family. It’s not like I’m fully retiring. I’m still gonna work a few shifts at my friend’s restaurant, garden, and play a lot of tennis.”

Do you know you have the most stars of any Chicago chef probably ever?

“Probably. I don’t know.”

Does that mean anything to you?

“Not really.”

Now I get personal, which I probably don’t need to do, but also I feel like a skeptical religious pilgrim witnessing a miracle.

So you don’t have any repetitive stress injuries?

“No.”

We talk about how Roland plays a lot of tennis. I ask him how he feels about pickleball, a sport I believe was invented for anyone over 40 because you don’t have to run too much.

“No. I don’t like it. I play tennis.”

I don’t mean for this to sound like Roland is ungrateful or he doesn’t care. He cares very much about the craft, making great food, collaborating, and taking care of his staff, just not any form of aggrandizement.

DeVries told me, “Roland continues to be generous 15 years later. He calls me one New Year’s Eve and says, ‘I cooked dinner for you.’ He drove to my house and dropped it off. It was classic 1980s French New Year’s food including lobster, and ribeye. It was such a random act of kindness, and then he’s like ‘I gotta go.’ and he disappeared.”

DeVries added, “There was a point I was working for him and I was constantly bending his ear about moving to Europe. It felt like he was brushing me off. One night I got really upset and threw a duck breast toward him during service, just a big no no. He isn’t really a big yeller, but that’s the first time he yelled at me. It turned out he was thinking about me. He was just waiting for the right time.

Two months later he takes me and some other cooks to Paris. We stay at his mom’s house. He got us stages at Pierre Hermé. We stayed at this apartment, it was me and a guy named Daniel Schatt. Roland would hang out with us, maybe there was some hash goin’ around. It was magic. We ended up working for one of Robuchon’s old pastry chefs making macaron, baguettes, and galette in the suburbs of Paris for a few months.”

4:30 p.m.

The Les Nomades kitchen does look straight out of Ratatouille with its burnt orange and cream tiles, and tiny copper sauce pans in varying sizes. It has a modern flat-lay out with relatively clean lines.

Unlike Ratatouille, there’s a printed photo of some goats blue-masking-taped to one of the sliding door coolers that says “The Goats. Paris, France.” I ask Brocar about it. He says he put it up and one of the food runners asked what it was and he told him “goats” and the food runner responded, “Oh, I thought they were dinosaurs.”

Kitchen humor. LOL.

Lopez, Depaz, and Gramajo have transformed like Superman from street clothes in to sharp well-cut Men in Black suits.

Mary Beth too is now in a smart pantsuit, wearing black, gold-trimmed ballet flats and a killer Hermes scarf that tells me she’s still the most stylish bird in the joint.

4:45 p.m.

Roland’s sous-vided soft-boiled eggs need to be peeled. Pastry assistant Anahi Torres Martinez comes over to help. Roland joins her. He puts on his clear-frame reading glasses, the kind with the magnet at the bridge that split so they can hang off your neck comfortably.

50+ years of cooking and he’s attacking this task like a hungry new commis. The eggs will be bathed in Manchego sauce and topped with a cotton candy cloud of shaved truffle.

A phone on wall in the kitchen rings a few times during the afternoon. No one ever answers it. It rings again, now. It remains unanswered.

Next to that wired landline is another anachronism, a dumbwaiter. Except this one is not stupid, it’s an actual electronically controlled mini-elevator for delivering food and other things to the second floor.

I ask Lopez if they had one of these at Trotters. He laughs and said, no, they had to run up and down stairs, and unlike Les Nomades, there were no platters underneath the plates providing balance. At Trotters they ascended the stairs, dishes directly in hand. Jostle a sauce swizzle or upturn a quenelle at your own peril.

Like a certain breed of 1990s high school weed dealers, the servers at Trotters also had old school pagers that beeped and vibrated to let the runners know it was time to pick up a plate.

5:00 p.m.

It’s go time. Fresh bread and a whole lot of the butter tufts I tried to eat like a dessert earlier during family meal make the first trip up to the second floor in the food elevator.

Roland asks me if I’m thirsty. I say yes, so he busts out some Pellegrino and pours it in a wine glass. I feel like an imposter dilettante. Everyone knows a real kitchen warrior drinks water from a plastic deli cup, not lithe stemware.

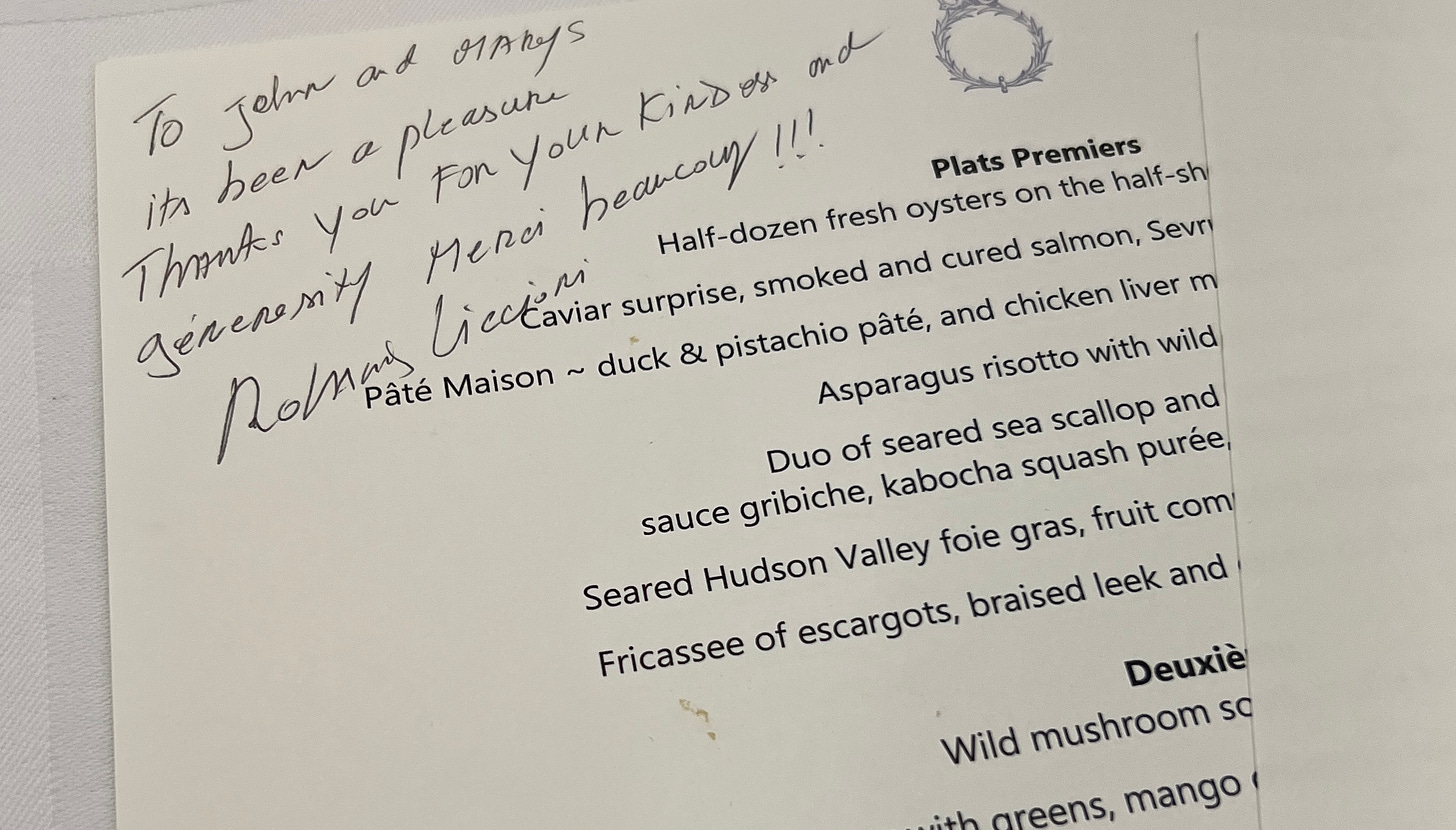

Two menus appear on serving platters. One is signed and inscribed by Roland for a couple of regulars. Someone, maybe Lopez or Mary Beth noticed that the menu got splashed with a little bit of sauce. Roland copies the inscription over and signs a new pristine menu.

Then as promised, Roland steps to the Vulcan range and starts firing duck breast on the line alongside the fish commis Miguel Martinez.

The pastry team, Torres Martinez and head pastry chef Alejandro Sanchez have already made their mignardise plates, so they’re bored as savory courses are fired. Dessert orders will come in a bit.

Torres Martinez tries to solve a pyramidal-shaped Rubik’s cube-like game while she waits. Sanchez, who makes one of the best Grand Marnier souffles in Chicago, clad in a Ford logo cap, leans against the counter.

5:15 p.m.

Roland works a couple sizzle pans of Peking-style duck lacquered in honey and mirin spiced with star anise and sauced with a lip numbing Sichuan peppercorn-infused gravy.

Staving off fat splatter flames Liccioni starts whistling And I Love Her by the Beatles. I am so privileged to be here in this moment. I want to be nowhere else, but also my middle-aged back is already a war zone. I look at the clock and estimate I only have five hours left.

One of us is an old man and it ain’t Roland.

The first plates arrive back from the dining room. Dishwashers Oscar Guaman and Francisco Duran don’t even wait for the runners to deliver the dirty dishes to the sink. They run over and grab them.

Gifts start rolling in for Roland from the dining room, bottles of wine and cards.

5:35 p.m.

The pass is humming. The first “all day” call goes out to confirm all the expected dishes being fired at each cooks’ station.

Roland sneaks me a tiny improvised banh mi made of foie torchon, pork pate, and cornichons stuck between a mini-crusty loaf.

He then turns to work on a plate of fat white asparagus and plump morels, slicing the stalks in to threes to build a triangle nest for the shrooms.

Then he leans over his caviar surprise, a mound of house smoked and cured salmon gilded with black pearls of caviar. He finishes the dish with a potato foam. He looks up, winks, and says, “Espuma! See, I can work at El Bulli if I want.”

6:45 p.m.

It’s super calm. There’s a couple of six top tables everyone is prepping for. Roland tells me a six top of regulars has dined at Les Nomades five times in the last two weeks just to get one more taste before he leaves.

Depaz and Gramajo ask Liccioni and Brocar to take an “última” night picture. I didn’t ask but I bet they also have one with Charlie Trotter filed away somewhere in a dresser printed on old school Kodak paper.

Gramajo asks me if I want to go up to the second-floor dining room and see what’s going on. After spending almost eight hours listening to the relentless hood fan and standing next to the flaming salamander or “broiler” in the kitchen, walking out to the serene front of the house feels like entering a sensory deprivation chamber. I haven’t seen this many neckties since prom.

Though the Les Nomades kitchen is relatively calm, it thrums with activity. Seeing this contrast between the front and the back of the house reminds me of exactly how much activity is expended to achieve this kind of serenity.

7:00 p.m.

Nicholas Butera, 31-year-vet of Les Nomades and its beverage director, who looks a little like Charlotte’s husband Harry Goldenblatt on Sex in the City, moves the first $1000 dollar bottle of wine of the night, and brings it back for Roland to see before delivering it to the guests.

7:15 p.m.

The kitchen is furiously firing the courses for the six-top. A server approaches Roland on the line and says there’s a table that wants to meet him.

He says, “I’m too busy.”

7:25 p.m.

Mary Beth arrives to negotiate a chef visit to the dining room. Roland looks exasperated. Mary Beth walks by me and says, “He’s not very social.” The six top plates go out. Roland walks to the front of the house to shake hands.

7:35 p.m.

Roland hooks me up with a couple of ribeye scraps drenched in a soul affirming au Poivre sauce. They’re served on the backside of a plastic deli cup. Now I feel like a real boy.

He turns back to the copper saucepans, adding water and tweaking seasoning. A sauce concentrating on the range is not the same at the beginning and middle of service. It must be constantly adjusted to maintain consistency throughout the night.

7:45 p.m.

Soufflés are now flying out of the kitchen like hot cakes. Actually not “like”. They’re actual hot cakes, huge sugar-crusted water balloons filled with egg custard teeming over the sides of silver ramekins bearing Roland’s monogram. They’re custom made in Lyon at the same place Paul Bocuse gets his silverware.

8:17 p.m.

Butera has upsold another $1000+ bottle of wine. Later on in the night I remark about his ability to move weight like this. He said, “Every night man. All the time. Lots of ‘em.”

There’s a table that’s been seated for a while and has not ordered. Roland says to me, “These guys used to come in to Le Francais at 8, and they’d talk and talk and wouldn’t order until 9:30.”

8:42 p.m.

A server comes in and says that one guest wants their third course, a short rib, to be boxed up for take-away so she can save room for soufflé. I would trust this person with my finances. They are very wise.

8:47 p.m.

I don’t know if it’s the heat of the salamander, but the Beatles And I Love Her is now playing at the back of the kitchen. Am I hallucinating? Maybe this is a Roland tradition, like his walk on and walk off music that he whistles before service and plays afterwards.

The intercom on the phone near the dumbwaiter crackles “Juanito. Juanito. Juanito, we need a soufflé upstairs now!”

Juanito slings it in the box and presses the second-floor elevator button.

9:01 p.m.

There are only a few covers to finish. Roland who has fired probably over 100 dishes himself this evening starts pouring off sauces from the little copper pans in to delis for next night’s service.

Donald Young of Duck Sel, his girlfriend Mimi Lie, and his friend and old Temporis partner Sam Plotnick arrive with Champagne to toast Roland.

I ask Young if Roland is always calm. Young says, no, sometimes he can get heated, but he’s usually pretty even tempered. He tells me about one night when Roland got feisty about something, but at the end of the evening was walking around the kitchen with two oranges behind his apron “like boobs” cracking everyone up.

I remark to Young and Plotnick about how I’m so tired and I don’t understand how Roland is still going. He only sat on a milk crate twice in the last nine hours. They nod in knowing and then Plotnick says, “One night he told some line cook ‘I’m three times your age and I’m working three times as fast’.”

9:15 p.m.

There’s still some soufflé and chocolate lava cake to be delivered, but Roland is about to plate the last dish of his full-time cooking career. Everyone gathers around like they’re witnessing Tom Brady with three seconds left on the clock working the Red Zone in the Super Bowl. Roland drops the sauce on another lamb duo and everyone claps and shouts “Ultimo!”.

9:35 p.m.

The champagne toasting begins. Roland savors it, but there are no tears, just a smile and a slight weariness.

10:02 p.m.

Roland disappears and then appears zipped up in a black winter coat. There are no hugs. He just waves goodbye and says, “I got to go home.”

10:15 p.m.

My work for the day is done, so I walk out the back, which unlike the majestic front of the restaurant is an industrial loading dock with a metal stairway. I walk around the corner on to Erie street and marvel that there’s a TGI Fridays so close to Les Nomades.

There should be a law against this like there is against selling liquor near a school. By order of the city, no chain restaurants, especially temples of flair, should be allowed within 500 feet of a grand dining temple like Les Nomades.

And yet, why so serious, Mike? What did you just learn? There’s room for everyone.

I met a god tonight and he was human like all of us. He was more than human. He was too busy with the things that mattered, but never too busy for the things that didn’t. I wanted to dwell on his glorious past and he only wanted to move forward.

The next night at dinner at Reno’s Pistores I was recounting the evening to my wife, and I started crying. Like I said I write because I’m searching for meaning. I’d finally found it in a way watching Roland’s retirement night.

I was happy that I saw all this, but I was sad that very few ever get to see the effort of running a restaurant. Every diner should do what I did once in their life.

They need the endorphin-rush of eating the best Grand Marnier-infused soufflé in the city while standing amidst a culinary team at the peak of their powers.

They need to see what a kitchen really is, not a centerfold of some six-pack-riddled chef in his boxer briefs in a glossy mag.

They need to see that a kitchen is composed of hardworking folks like Juan who raised kids and helped put them through college as a service professional.

They need to see Bakou escaping the oppression of a violent government and building a life in America one charcuterie plate at a time.

They need to see Jack earnestly and gingerly stepping in to the Shaq-sized sneakers of a legend.

A diner needs to see Mary Beth worrying so they don’t have to.

Then and only then will they know the true price and value of their meal.

When this was all over, it was hard not to think, “Welp, there goes the last great Chicago restaurant dynasty!”

But then a friend DMed me on Saturday night. She’d had dinner at Les Nomades the first day after Roland’s departure.

She said, “Was glad to be back there tonight. The foie gras and lobster salad were perfection. Soufflé was magic. The chef tonight did a great job. Terrific new chapter.”

Les Nomades is dead.

Long live Les Nomades!

—

Les Nomades is located at 222 E. Ontario in Chicago

To say damn you're good, would be an understatement!

Happy you put your big boy pants on, a jacket and showed up.

Thanks for writing this masterful piece for us to enjoy. Long live Les Nomades is right. Roland’s story and how he got here is one many should read. Truly fascinating. Cuisinier. True legend.

This is such a great article, Michael. You should be proud. You’ve captured the essence of Roland and Mary Beth, and illustrated their specialness and the specialness of Les Nomades. I’ve got a great Roland Liccioni story that goes back to 2011!